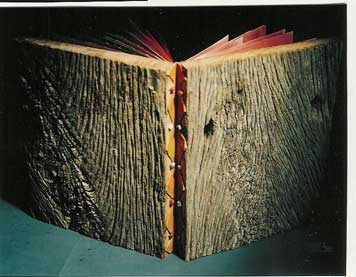

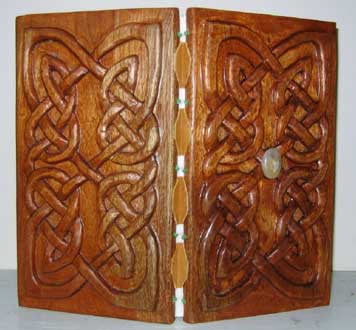

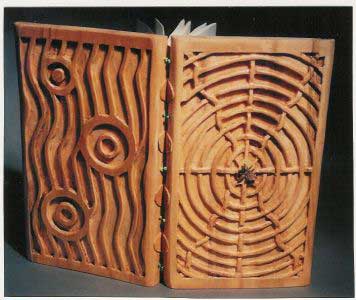

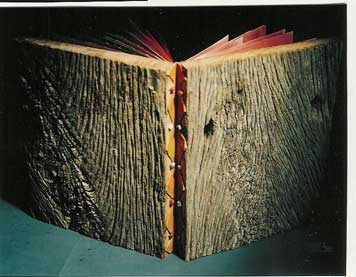

Books Made Out of Wood

February 25th, 2007 at 12:09 pm (Books)

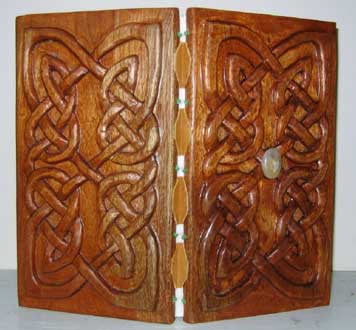

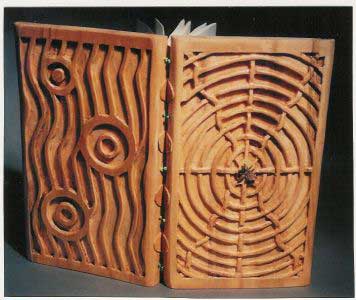

Librarian.net points to “a new kind of book blog”. Barbara Yates makes books out of wood. Some of these are quite lovely:

To see more, visit Barbara’s site.

February 25th, 2007 at 12:09 pm (Books)

Librarian.net points to “a new kind of book blog”. Barbara Yates makes books out of wood. Some of these are quite lovely:

To see more, visit Barbara’s site.

February 22nd, 2007 at 8:00 pm (Writing)

It was late last year that I realized I could potentially make a living writing for the web. It was today that I knew that this was true. I make a modest (but decent) income at the box factory. But for the last week, my web income has equaled my income from my real job. Scary, huh?

Now this is just one week. Though I’m making good money from my writing, there are many ups and downs. But even the lows are higher than I could have imagined. On November 25th, I made $29.29 in web income. That is the last day my earnings dipped below $30. My best day was last Tuesday: I made $169.90.

Over at 2blowhards (still one of my favorite blogs), Michael writes:

Planning on getting rich writing sci-fi or fantasy novels? Think again. Tobias Buckell writes that the average advance for a first sci-fi or fantasy novel is $5000. Five years and five novels later, the average author is pulling in around $13,000 per novel.

I used to want to get rich off writing sci-fi or fantasy. Then I decided I just wanted to get rich off writing books — I didn’t care what kind. More and more, it’s clear that I may never publish a book (at least not in the traditional sense)! I’m already making twice what a sci-fi novelist makes, and I have complete control of my content. There’s little motivation for me to change directions at the moment.

Some people — and perhaps you’re one of them — look disdainfully upon web income. “You’re not making money from writing,” is a common observation. “You’re making money from advertising.” I can understand this delineation, but it’s not one that I make.

I am writing, and publishing that writing, and it’s making me money. I don’t feel guilty about it. I don’t feel as if I’m compromising anything. Did I ever dream I’d make a living writing about personal finance? Nope. But now I can’t imagine anything else I’d rather be doing.

February 20th, 2007 at 10:55 am (In the News, Libraries)

Will Sherman writes at DegreeTutor.com that librarians are not obsolete. In fact, he offers a list of 33 reasons that libraries and librarians are still extremely important.

Many predict that the digital age will wipe public bookshelves clean, and permanently end the centuries-old era of libraries. Technology’s baffling prowess and progress even has one librarian predicting the institution’s demise. He could be right.

But if he is, then the loss will be irreplaceable. As libraries’ relevance comes into question, they face an existential crisis at a time they are perhaps needed the most. Despite their perceived obsoleteness in the digital age both libraries — and librarians — are irreplaceable for many reasons. 33, in fact. We’ve listed them here.

The list — minus Sherman’s elaboration on each point — is as follows:

Much of this list is defensive. Moreover, parts of it are examples of poorly-reasoned wishful thinking: “It can be hard to isolate concise information on the internet”? Give me a break. If it’s hard to isolate concise information on the internet, I guarantee it’s more difficult to isolate concise information in a library. And it will take days instead of minutes. I think the aspects of the list that emphasize human interaction and the preservation of book culture are more convincing than those denigrating the internet.

But I mostly agree with the author’s main point: librarians and libraries are a necessary and vital resource, even in today’s increasingly digital world. I give the librarians I know a hard time because they all seem to be on a holy crusade, convinced that their profession is the noblest of all. In reality, I appreciate their work. To learn more about each of these 33 points, read the entire article.

[DegreeTutor.com: Are librarians totally obsolete?]

February 18th, 2007 at 10:27 am (Authors, Funny Stuff)

Neatorama recently published a list of authors who write in the buff. I guess I shouldn’t be surprised, but do I really need to know that Hemingway wrote A Farewell to Arms in the nude? Yikes!

The list includes:

Commenters to the post noted others authors who were purported to feel the muse while in the buff: Sherwood Anderson, Harlan Ellison, and historian Forrest McDonald. I may sit around writing in my undies (sorry — too much information, I know), but naked? I’d get cold!

[Neatorama: The naked truth: Authors who write in the buff]

February 15th, 2007 at 10:09 am (Reviews, Success)

There’s a famous story of a young woman who dined one evening with William Gladstone, and the next evening with Benjamin Disraeli. (Gladstone and Disraeli were prominent British statesmen of the nineteenth century. They were bitter rivals.)

Asked her impression of these two powerful men, the young woman said, “When I left the dining room after sitting next to Mr. Gladstone, I thought he was the cleverest man in England. But after sitting next to Mr. Disraeli, I thought I was the cleverest woman in England.”

This anecdote illustrates the message at the heart of Dale Carnegie’s classic How to Win Friends and Influence People. To win others to your way of thinking, put yourself in their shoes.  See life from their perspective.

See life from their perspective.

This is easier said than done. We are each wrapped up in our own lives. We have our own goals and our own worries. It’s difficult to surrender ego for the sake of another person. Yet that’s the key to dealing with people: Do unto others as you would have them do unto you. The Golden Rule, says Carnegie, is prevalent in nearly every culture, and is the basis for dealing with others.

How to Win Friends covers four broad topics:

Each of the book’s chapters has a title that sounds like a link-baiting weblog entry. Each chapter offers a catchy maxim. This makes the entire text easy to boil down to outline form, which I’ve done below. (Doing this tosses aside the essential flavor of the book, though. I encourage you to read it.)

Fundamental Techniques in Handling People

This introductory section gives a broad overview of Carnegie’s topic, and establishes the three core tenets of his philosophy.

Six Ways to Make People Like You

In this section, Carnegie covers the basic skills for getting along well with others. These techniques are useful under any circumstance.

Twelve Ways to Win People to Your Way of Thinking

What’s the best way to settle a disagreement in your favor? My mantra is: If you want to defeat your enemy, sing his song. Carnegie’s approach is similar:

Nine Ways to Change People Without Giving Offense or Arousing Resentment

The book’s final section suggests techniques for changing other people.

Early editions of the book include an additional section describing “Seven rules for making your home life happier”. I suspect this content was removed for fear of stirring up a hornet’s nest. It does little more than rehash the previous sections, anyhow.

Each time I read the How to Win Friends, I get the impression that Carnegie ran out of steam toward the end. The first half is packed with letters and stories that elaborate his points. Later chapters are brief. Some are only a page long. This puzzles me, and weakens the book somewhat, but not enough to ruin it.

I enjoy How to Win Friends and Influence People. I read it at least once a year. It’s an easy book to mock — its earnest tips can seem idealistic and childish to the cynical — but its advice is straightforward and practical.  Best of all, this book is readable. Carnegie has an easy, personable style, and he fills each chapter with engaging anecdotes from students and readers who have put his precepts to action. (Later editions are charming because they intermix the best stories from the original 1936 edition with anecdotes from the 70s and 80s — it’s fun to read a story about a computer programmer followed by a story of a man who’s trying to sell “motor cars”.)

Best of all, this book is readable. Carnegie has an easy, personable style, and he fills each chapter with engaging anecdotes from students and readers who have put his precepts to action. (Later editions are charming because they intermix the best stories from the original 1936 edition with anecdotes from the 70s and 80s — it’s fun to read a story about a computer programmer followed by a story of a man who’s trying to sell “motor cars”.)

This book is easily misinterpreted. I’ve heard it condemned for encouraging people to be obsequious flatterers. Yet Carnegie loathes insincerity. He doesn’t want his readers to turn into toadies; he wants his readers to genuinely learn to think in terms of other people’s interests. His goal is a “win-win” situation.

How to Win Friends, first published in 1936, is just as relevant in 2007 as it was seventy years ago. Because it was one of the most popular books of the twentieth century, copies are easy to find cheap at book stores, thrift shops, and garage sales.

From the Wikipedia: “Dale Carnegie (November 24, 1888 - November 1, 1955) was an American writer and the developer of famous courses in self-improvement, salesmanship, corporate training, public speaking and interpersonal skills. Born in poverty on a farm in Missouri, he was the author of How to Win Friends and Influence People, first published in 1936, a massive bestseller that remains popular today. He also wrote a biography of Abraham Lincoln, titled Lincoln the Unknown, as well as several other books.”

February 12th, 2007 at 5:42 pm (Authors, Biography)

Leafing through my back issues of The New Yorker, I found another review of Claire Tomalin’s Thomas Hardy, which I mentioned a couple weeks ago. Actually, this piece appears to be less a book review and more a mini-biography of Hardy. I don’t have time to read the article at the moment — it’s quite long — so I’ve torn it out for later digestion. It’s available online: “God’s Undertaker: How Thomas Hardy became everyone’s favorite misanthrope” by Adam Kirsch.

February 10th, 2007 at 7:57 pm (Biography, Book Group, History)

The Elm Street Book Group met today to discuss Undaunted Courage, a biography of Meriwether Lewis by Stephen Ambrose. We found the narrative of the Lewis and Clark expedition exciting and worth reading, but the other sections of the book seemed to engender less admiration. Most of the group had complaints about Ambrose and the persistent intrusion of his editorial voice. Many of his asides are at odds with the facts. Others are racist, or sexist, or simply puzzling. I was bothered by how enamored Ambrose seems to be with Meriwether Lewis. As a piece at Slate says:

The Elm Street Book Group met today to discuss Undaunted Courage, a biography of Meriwether Lewis by Stephen Ambrose. We found the narrative of the Lewis and Clark expedition exciting and worth reading, but the other sections of the book seemed to engender less admiration. Most of the group had complaints about Ambrose and the persistent intrusion of his editorial voice. Many of his asides are at odds with the facts. Others are racist, or sexist, or simply puzzling. I was bothered by how enamored Ambrose seems to be with Meriwether Lewis. As a piece at Slate says:

You’ll search Undaunted Courage long and hard for evidence that Meriwether Lewis wasn’t a saint or that the Lewis and Clark expedition wasn’t the most important and glorious event in early American history.

Ambrose constantly praises Lewis’ excellent qualities. He repeatedly ignores his flaws. Whenever Lewis makes an obvious mistake that must be commented upon, Ambrose dismisses it as out of character. Yet I believe that the pattern of these mistakes is indicative of character.

For large stretches of the expedition, there is no surviving record from Lewis. We have only Clark’s words to go by. When Lewis does keeping score, the picture he paints of himself is not as rosy as Ambrose supposes. Here are just a few instances that occur to me off the top of my head:

Lewis has ongoing problems with drinking, gambling, and debt. Ambrose deals with these issues, but in a cursory fashion. I think it’s damning that Lewis is unable to establish a relationship with a woman. Women seemed unwilling to be around him. Why is this? What was there about him that they found so distasteful? I believe he must have had some character flaw.

We discussed how Lewis seems brash and self-assured. He rushes into things. Clark seems to be calmer and a better planner. Whenever they separate, it is Lewis that gets into trouble and Clark who makes it through without incident.

Then there’s Lewis’ complete inattention to duty once he returns from the expedition. He ignores his charge to publish the journals. He spends more than a year as governor of the Louisiana Territory doing nothing.

Undaunted Courage reminded us of The Last of the Mohicans, which we read last year. The frontier adventure, the savagery of the Indians, and the closeness to nature are all similar. In order to highlight the mortality rate of frontiersman, I noted that most of the expedition’s crew members were dead within a decade of returning, some within just a year or two. (And many at the hands of Indians.)

We discussed the clash of cultures. Why did Americans look at Blacks as less-than-human, but consider Indians merely uneducated brethren? Was it skin color? Location? Something else?

I’m under the impression that most of the group enjoyed the book. We found it instructional and entertaining. We just had complaints with Ambrose’s editorial voice. A few of us would have rather had read the journals of Lewis and Clark themselves.

Finally, Rhonda noted that Ambrose was criticized for plagiarism when writing this book.

The Elm Street Book Group has been meeting once a month for over a decade. (We started in November 1996.) Kris selected this book. We held a brunch discussion at our house. In attendance: Kris, J.D., Bernie, Kristi, Lisa, Rhonda, Courtney, Jason, Naomi, Tiffany. Next month: The Long Emergency by James Howard Kunstler (who has a blog called Clusterfuck Nation). April: Life With Father and Mother by Clarence Day.

February 9th, 2007 at 1:55 pm (Writing)

I have several Bibliophilic articles in production, but meanwhile here’s the ultimate guide to conquering writer’s clock, which is a collection of inspirational links.

The good news is every author in the world deals with it, and the web is full of useful tips for beating it. I’ve collected the best of them for you here, to help you whenever you’re battling the blank screen.

This is an excellent resource, one I’m sure to use once or twice a month.

[Bestseller Interviews: The ultimate guide to conquering writer's clock]

February 5th, 2007 at 6:53 am (Classics, Lists)

I once knew a man who claimed to have read every book in the English canon.

I took a writing class at Clackamas Community College in the fall of 1995. One of my classmates was an Hispanic man for whom English was a second language. This fellow loved to read and he loved to write, but felt his grasp on both was rather tenuous. How could he improve? He decided to read every great book in the western canon. To this end, he found a list of the hundred greatest books and, over the course of several years, he read them all.

Obviously, any such list of “the hundred greatest books” is going to be, by its very nature, somewhat limited and somewhat arbitrary. This is irrelevant. The point is this man had picked a pool of great books, had read them, and he was much the better for it. Of all my writing classmates, his stories had the greatest depth and texture. Was this solely because of his reading experience? Probably not, but I’m certain that his breadth of knowledge helped him.

How could it not?

I’ve come to view the whole of literature as a vast, interconnected web. Mortimer Adler and Robert Hutchins, in their The Great Books of the Western World, termed this “The Great Conversation”, a dialogue between authors which spans centuries. (Millennia!)

If you are new to the classics, this great conversation is not immediately apparent. If, say, you pick up and read (as your first classic) Thomas Hardy’s Jude the Obscure, the book’s connection to the western canon is not visible. You don’t know what to look for.

The more classics you read, the more apparent the connections become.

Maybe you read a dozen more books, and familiarize yourself with the plots and details of twenty more. If you then pick up Jules Verne’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, you’ll begin to sense tiny filaments connecting the novel to others you’ve read; you’ll note references to The Odyssey and The Tempest; or, looking forward, hints of things to come in Crime and Punishment and The Stranger. (What’s more, you’ll begin recognize connections to stories outside the canon — isn’t Disney’s 1978 film The Black Hole nothing more than 20,000 Leagues in space? Is this intentional?)

Eventually, you will have read a large portion of the canon. (Half, let’s say.) Now when you read a classic, the threads connecting it to other great works are obvious and everywhere. (They were there before, but you hadn’t the experience to note them.) You can not only see the connections to books you’ve read, but you can also sense connections to books you haven’t read. Sometimes you know where the connection leads (”Oh, a reference to Becky Sharp. Gosh, I need to read Vanity Fair sometime.”), sometimes you don’t (”I wonder what this whole thing about a madeline is…”).

Moreover, references to the canon abound in everyday life. (At least in my everyday life.) The more you are familiar with the great books, the more you notice these references, the richer your everyday experience becomes. Sure, an average issue of Harper’s or The National Review is laden with classical allusions, but even a copy of Time or Newsweek or — gasp — Entertainment Weekly contains several references to literature. The greater your familiarity with the canon, the more of these references you catch, and the richer your reading experience, even if you’re only reading an article that makes a passing comparison of Madonna to Becky Sharp.

Why the rhapsody about English Lit?

Last night we watched the recent film adaptation of Vanity Fair. Actually, to begin with, Kris watched while I used my laptop to surf the internet. I paid only a sliver of attention. As the movie progressed, I found myself drawn into it. Though it was obviously watered down, I could sense the “great book” quality beneath it. Eventually I was fully engrossed in the story, and I regretted having not paid attention earlier — how are these Crawley people related to Pitt?

The western canon is a very real presence in my life. I have three books that contain reading lists constructed from the canon, my favorite of which is Clifton Fadiman’s The Lifetime Reading Plan.

Lisa and I discuss this book from time-to-time. We both like it, but we don’t like some of the recent changes. I have the third edition, and like its reading list, but I think Lisa has the fourth. While the structural changes to the list between editions makes sense (works are now organized chronologically rather than by type), we think the changes to the reading list’s content are more for political correctness than for quality.

(Tangent: I’m all in favor of an inclusive canon, one which represents of all genders, creeds, and colors, but not at the expense of quality. It is a part of our history that certain segments of the population were oppressed. The remedy to this situation is not to rewrite the past, to argue that works of lesser quality deserve a place in the canon simply because they’re written by someone who was oppressed at the time; the solution is to allow these people to craft a legacy now, to encourage them to create works that will stand the test of time. A stop-gap measure is one in common practice: the creation of specialized “mini-canons” featuring, for example, the best writing by women through the centuries, etc. I believes a rich cultural history is evident when one is able to look at the canon and see, with the advent of Jane Austen, the presence of women in the canon. This tells a story, and an important one.)

It’s surprisingly difficult to find comprehensive reading lists on the web. Some brief googling revealed the following:

Whichever list you choose, the important thing is to begin reading the classics today. Your life will be the better for it.

February 2nd, 2007 at 8:21 am (Authors, In the News, Publishing)

Last weekend The New York Times featured a pair of stories about Victorian literature.

The first is a review of the “Victorian Bestsellers” exhibit at the Morgan Library & Museum.

Some of these best sellers are now barely known… Other best sellers remain literary landmarks. After Charles Dickens’s Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club began appearing in monthly installments in March 1836, its press run increased from 1,000 copies for the first part to 40,000 for the finale in October 1837. By 1879 the full novel had sold 800,000 copies and had transformed British publishing.

The exhibition is a bit constricted by taking Queen Victoria’s reign (1837-1901) as its domain, since, as it acknowledges, the prime example of a best-selling author was Sir Walter Scott, whose 1819 Ivanhoe (part of the author’s manuscript is on display here) sold 10,000 copies in two weeks.

But this show — suggestive and alluring, with its sampling of the Morgan’s riches — demonstrates that it was during the latter part of the 19th century that the appetite of a growing public was institutionalized, and that authors and publishers knowingly worked for large sales, perfecting new forms of packaging for print.

I love this piece because although I’ll never see the exhibit in question, it gives me some background on publishing history that I otherwise might have missed.

The other Times article reviews a new Biography of Thomas Hardy. The reviewer proclaims Claire Tomalin’s Thomas Hardy “excellent”.

This new biography makes its subject a fascinating case study in mid-Victorian literary sociology. Hardy struggles — with an industriousness befitting the age — against editorial rejection, rapacious contract terms and enforced prudery. Leslie Stephen, known chiefly to the 21st century as Virginia Woolf’s father, edited his magazine, The Cornhill, under the watchful, prissy eyes of so many others that he sometimes made “few suggestions beyond bowdlerizations†when working on Hardy’s copy. Serialization often forced the author “to pack in far too much plot†and thereby throw novels like The Mayor of Casterbridge significantly off-kilter. Finally, there were reviewers to contend with; Hardy remained overly sensitive to all they had to say.

There are but a few authors about which I collect supplementary books — Proust, Austen, Dickens — but Thomas Hardy is one of them. I recently re-read

The Return of the Native and loved it. Hardy captures rural country life perfectly. And though he’s writing about mid-19th century England, I feel as if he’s actually writing about the rural Oregon countryside where I grew up. I am eager to read this biography.

[The New York Times: Best-seller big bang: When words started off to market and Thomas Hardy's English lessons, both links from Bibliophilic reader Paul]